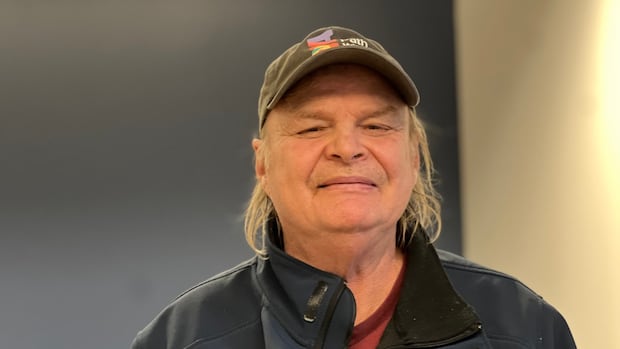

When William Lester Jr. decided to get into a 12-week program to tackle his drug use, he said that he had only weighed £ 68. The residents of Seattle, Washington, has used Heroin for 35 years and recently also methamphetamine.

He knew that something had to change when he was admitted to the hospital for kidney failure.

“I was not ready for years until one day I said: ‘I’m done, I can’t do that anymore,” said Lester, who lives in supporting apartments in Seattle.

He attributes to his case clerk for the path of an emergency management program, which rewards the abstinence of stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine with gift cards.

Gift cards twice a week

The program, which works in states such as California, Montana and Washington, calls on the participants to give a urine sample and carry out a short test to determine whether it is using drugs in the past few days.

The patient receives a reward for each negative test. In the state of Washington and Plymouth Housing in Seattle, where Lester lives, this reward comes in the form of gift cards.

“It is a little unusual because it is a procedure in which the person comes in and usually has a really positive, entertaining interaction with the clinician” at the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine at Washington State University.

“If it shows that the person has not used stimulants in the past few days, they have a really big celebration and give this person a gift card,” said McDonnell.

For every negative urine sample that takes place twice a week, the patient receives a gift card worth 12 US dollars. And the crowd gradually increases with every negative test. The participants can receive a maximum of 599 US dollars per calendar year.

If a patient tests positively for medication, they are not thrown out of the program. Instead, your gift card decreases and you have to rebuild your way.

With the gift cards, food, clothing or even electronics can be bought.

Emergency management has decades of success for success to help people stop or reduce their stimulants drug use, says McDonnell.

The program is administered from clinics, except in Seattle, where it works outside of Plymouth Housing, a constant supportive non -profit organization for apartments for people who have to deal with long -term homelessness. 40 people have been pursued there for more than a year.

In Plymouth, the goal is to bring the program to people instead of going to an outpatient clinic.

According to Aaliyah Bains, the program manager for behavioral health at Plymouth Housing, this is great.

“It was not easy to just take it out of the clinical environment and push it into the living space,” she recalls. But it works.

“We actually have higher participation rates and higher completion rates than in clinical environments,” said Bains and refers to provisional data.

Another difference lies in the fact that it is a peer support worker in Plymouth who comes to the unit of the resident, which means that they are seen by someone who has experienced addiction himself.

“I was in AA, too many such things, but you see, I can’t refer to someone who was not there”.

Participation was not always easy. Lester says he thought he could cheat the system, but was surprised to stick to it.

“I stopped (with drugs) thanks to the program”.

With increasing discussion about involuntary drug treatment in Canada, Julia Wong from CBC in Washington State is going to learn something about Ricky’s law and the challenges to force people in rehab.

Evidence -based approach

The majority of the evidence of emergency management comes from decades of research on veterans.

The US veterans -affair department has implemented the program in 2011. However, the settings – such as looking at rewards as bribes – slows down their use for the general public.

Things changed when overdosing epidemic became a crisis of public health.

California was the first state to cover emergency management under Medicaid and “evaluate the effectiveness of treatment on a scale”, according to the California Ministry of Health.

In 2021, the Montana and Washington states started the program on a large scale for stimulant disorders.

In the state of Washington, 24 clinics offer the 12-week program. Preliminary results show that, according to McDonnell, around 70 percent have been involved by more than 200 participants and their consumption of stimulants were reduced.

Information tomorrow – Fredericton14:40Clinical meth study

It is the largest clinical study in the world to use methamphetamine and the River Stone Recovery Center in Fredericton will take part. J Eanne Armstrong spoke to Dr. Sara Davidson. https://www.cbc.ca/canada/new-brunswick/fredericton-stone-centre-trial-meth-1.7230339 (https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswrun/ Fredericton-River-Stone-Center-Trial-1.7230339)

British Columbia also has some emergency management programs, although very limited.

“It is an important part of the continuum of supplying substance use,” said a spokesman for the Ministry of Health in a statement.

The BC programs are carried out by Vancouver Coastal Health and Fraser Health and include a 12-week group consulting program carried out by AIDS Vancouver. Most of them focus on the use of stimulants.

The need for effective treatment programs has become more urgent in recent years because the toxic drug crisis has deteriorated.

Although fentanyl and other opioids have made all the headlines in Canada and North America since 2016, stimulants are also overdose in a growing proportion of deaths. In Canada, in addition to opioids in 64 percent of the deaths of toxic drugs, stimulants were found in 2024.

In the same year in BC, cocaine was detected in 52 percent of the overdosed toxicologists and methamphetamine was found in 43 percent.

A new report showed that after the beginning of the Covid 19 pandemic, deaths in Ontario exceeded several substances by overdosing through a single substance.

Bains says that emergency management gives people the opportunity to be successful with something.

“So many programs are all or nothing, they have to be 100 percent sober or they are not successful. It is simply not what emergency management is.”

Bains also experienced the pride of some of the 40 participants of the one-year Plymouth pilot project.

“I saw that people have changed. If they give them the opportunity to have $ 20 a week for someone who has no income, life changes.”

Housed patients who are more finished

While one believes that financial rewards for wealthier patients would not work so well, McDonnell has proven to be a strong incentive regardless of income.

“I have doctors, lawyers and other people who are very well financially compensated for but are really desperate to use their substances … and they are motivated by the idea that they are rewarded,” said the researcher.

If at all, it is uncontrolled people who perform poorly in the emergency management program.

“It is less likely to end the program because you have so many other things you have to do with,” said McDonnell. And he added that they could rely on stimulants to keep them awake out of safety.

“It is dangerous to be homeless: someone could come and steal their things, they could be attacked,” said McDonnell.

According to Lester, he made him the likelihood that he was housed in Plymouth for six years.

Although it was a low income, the incentives are less important than the process of responsibility and believing that someone believes in their success.

“I could tell you that I feel better now than I ever felt in my whole life,” he said proudly.