The Russian military prepared detailed lists of targets for a possible war with Japan and South Korea that included nuclear power stations and other civilian infrastructure, according to secret files from 2013-2014 seen by the Financial Times.

The strike plans, outlined in a batch of leaked Russian military documents, cover 160 locations such as roads, bridges and factories, chosen as targets to stop “regrouping of troops in areas of operational intent”.

Moscow’s acute concern for its eastern flank is highlighted in the documents, which were shown to the FT by Western sources. Russian military planners fear that the country’s eastern borders would be exposed in any war with NATO and vulnerable to attacks by US assets and regional allies.

The documents were drawn from a cache of 29 secret Russian military files, mainly focused on training officers for potential conflict on the country’s eastern border from 2008-14 and are still seen as important to Russian strategy.

The FT reported this year how the documents contain previously unknown details on the operating principles for the use of nuclear weapons and outline scenarios for war games on a Chinese invasion and for attacks deep inside Europe.

Asia has become central to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s strategy to pursue a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and his broader anti-NATO stance.

In addition to increased economic support from China, Moscow has recruited 12,000 troops from North Korea to fight in Ukraine, while in return it strengthens Pyongyang economically and militarily. After firing an experimental ballistic missile into Ukraine in November, Putin said that “the regional conflict in Ukraine has taken on elements of a global nature.”

William Alberque, a former NATO arms control official now at the Stimson Center, said that, together, the leaked documents and North Korea’s latest deployment proved “once and for all that the European and Asian theaters of war are directly and inextricably linked”. “Asia cannot sit back from the conflict in Europe, nor can Europe sit idly by if war breaks out in Asia,” he said.

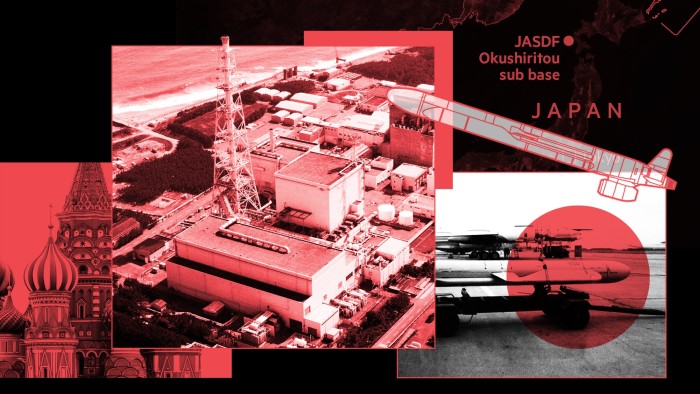

The list of targets for Japan and South Korea was contained in a presentation intended to explain the capabilities of the Kh-101 non-nuclear cruise missile. Experts who reviewed it for the FT said the content suggested it was distributed in 2013 or 2014. The document is marked with the markings of the Combined Arms Academy, a training college for senior officers.

The US has significant forces amassed in South Korea and Japan. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the two countries have joined the Washington-led export control coalition to pressure the Kremlin’s war machine.

Alberque said the documents showed how Russia perceived the threat from Western allies in Asia, which the Kremlin fears would stop or enable a US-led attack on its military forces in the region, including missile brigades. . “In a situation where Russia would attack Estonia out of the blue, it would have to hit US forces and boosters in Japan and Korea as well,” he said.

Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s spokesman, did not respond to a request for comment.

The first 82 sites on Russia’s target list are military in nature, such as the central and regional command headquarters of the Japanese and South Korean armed forces, radar installations, air bases and naval installations.

The rest are areas of civil infrastructure, including road and rail tunnels in Japan, such as the Kanmon Tunnel connecting the islands of Honshu and Kyushu. Energy infrastructure is also a priority: the list includes 13 power plants, as well as nuclear complexes in Tokai, as well as fuel refineries.

In South Korea, the main civilian targets are bridges, but the list also includes industrial sites such as the Pohang steel mills and chemical plants in Busan.

Much of the presentation is about how a hypothetical strike might unfold using a non-nuclear Kh-101 warhead. The example chosen is Okushiritou, a Japanese radar base on a hilly offshore island. One slide, discussing such an attack, is illustrated with an animated gif of a large explosion.

The slides reveal the care Russia took in selecting the target list. A note against two South Korean command and control bunkers includes estimates of the force required to breach their defenses. The lists also note other details such as the size and possible production of the objects.

Photographs of the buildings at Okushiritou, taken from inside the Japanese radar base, are also included in the slides, along with precise measurements of the target buildings and objects.

Michito Tsuruoka, an associate professor at Keio University and a former researcher at Japan’s Defense Ministry, said the conflict with Russia was a particular challenge for Tokyo if it was the result of the conflict spreading from Europe to Russia – the so-called “escalation horizontal”.

“In a conflict with North Korea or China, Japan would receive early warnings. We can have time to prepare and try to take action. But when it comes to a horizontal escalation from Europe, there will be a shorter warning time for Tokyo and Japan would have fewer options on its own to prevent conflict.”

While the Japanese military, and air force in particular, has long been concerned about Russia, Tsuruoka said Russia is “not often seen as a security threat by ordinary Japanese.”

Russia and Japan have never signed a formal peace treaty to end World War II because of a dispute over the Kuril Islands. The Soviet military occupied the Kuriles at the end of the war in 1945 and expelled Japanese residents from the islands, which are now home to about 20,000 Russians.

Fumio Kishida, Japan’s then prime minister, said in January that his government was “fully committed” to negotiations on the issue.

Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s former president, said on X in response: “We don’t give a damn about the ‘feelings of the Japanese’. . . These are not ‘disputed territories’ but Russia.”

Russia’s plans show a confidence in its missile systems that has since proven to be overstated. The hypothetical mission against Okushiritou involved the use of 12 Kh-101s launched from a single Tu-160 heavy bomber. The document estimates the possibility of destroying the target at 85 percent.

However, Fabian Hoffmann, a PhD researcher at the University of Oslo, said that during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Kh-101 proved less stealthy than expected and struggled to penetrate areas with layered air defenses.

Hoffmann added: “The Kh-101 features an outboard motor, which is a common feature of Soviet and Russian cruise missiles. However, this design choice significantly increases the missile’s radar signature.”

Hoffmann also noted that the missile had proved less accurate than expected. “For limited-yield missile systems that rely on pinpoint accuracy to destroy their targets, this is an obvious problem,” he said.

A second presentation on Japan and South Korea offers a rare insight into Russia’s habit of regularly probing its neighbors’ air defenses.

The report summarizes the mission of a pair of Tu-95 heavy bombers sent to test the air defenses of Japan and South Korea on February 24, 2014. The operation coincided with the Russian annexation of Crimea and a joint US-Korean military exercise, Foal Eagle 2014.

The Russian bombers, according to the filing, took off from the Ukrainka Long-Range Aviation Command base in the Russian Far East for a 17-hour circuit around South Korea and Japan to record responses.

He points out that there have been 18 interceptions involving 39 aircraft. The longest encounter was a 70-minute escort by a pair of Japanese F4 Phantoms, which, according to the Russian pilots, “were not armed.” Only seven of the intercepts were made by fighter jets carrying air-to-air missiles.

The route almost identically matches that taken by two Tu-142 maritime patrol aircraft earlier this year when they circled Japan during strategic exercises in the Pacific in September, including a flight over the disputed area near the Kuriles.