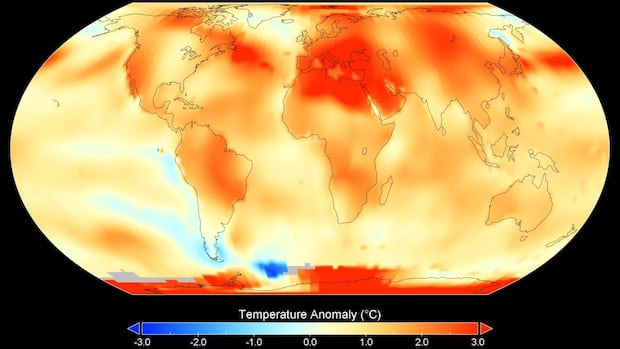

Today, six climate agencies from around the world confirmed what we expected: Earth was once again experiencing its hottest year on record.

But whether or not it was 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average depends on which climate agency you look at.

According to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, 2024 was the warmest year on record since 1850, 1.6°C above the pre-industrial average (1850-1900). It surpassed 2023 as the warmest year on record, which was 1.48C warmer than the pre-industrial average.

However, according to NASA, in 2024 it was 1.47 °C warmer than the pre-industrial average and continued to settle at 1.5 °C.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) found it was 1.46°C warmer.

Berkeley Earth, a nonprofit climate analysis organization, also found that in 2024 it was 1.62 degrees Celsius warmer than the pre-industrial average.

The numbers vary by agency because of the way climate agencies collect past data.

However, the World Meteorological Organization looked at all of these analyses, as well as those from the UK’s Met Office and Japan’s Meteorological Agency, and found that warming is “likely” to exceed 1.5°C in 2024.

However, there is consensus that the last decade has been the warmest on record.

However, this could be the first calendar year in which the EU limit of 1.5°C is exceeded Paris Agreementthat does not mean we have broken this agreement. This threshold – the commitment by 195 countries to keep global warming below 1.5°C of the pre-industrial average – applies to many years in which the Earth’s temperature is consistently above it, rather than just one or two.

And that doesn’t mean there’s no hope of preventing warming beyond that goal. As climate scientists often say: “Every fraction of a degree counts.”

This is not the first 12-month period in which warming exceeds this threshold. From mid-2023 to mid-2024, the planet was 1.5°C warmer. It’s just that it hasn’t happened over the course of a calendar year.

Does 1.5 really matter?

While there is disagreement about exactly how warming is in the hundredths of a degree range, the message is the same: the Earth is getting warmer.

“What I think we can say is that it is likely that the 1.5 limit will have been exceeded in 2024,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “However, the effects we see when they are around 1.48 or 1.52 or 1.6 are pretty much the same.”

“We see increasing rainfall intensity, we see increasing heat waves, we see sea level rise. “All of these things don’t really depend on the little details of that last decimal,” he told Schmidt.

According to World Weather Attribution (WWA), climate-related disasters contributed to the deaths of at least 3,700 people and the displacement of millions in the 26 weather events studied in 2024.

In its December report, the WWA noted: “These were just a small fraction of the 219 events that met our trigger criteria that we used to identify the most influential weather events. It is likely the total number of people killed in extreme weather events amplified by climate.” The change this year is in the tens or hundreds of thousands.

When will we know we have crossed the Paris Agreement threshold?

While 2024 began with high temperatures fueled by an El Niño – a natural, cyclical warming in a region of the Pacific Ocean that, combined with the atmosphere, can cause global temperatures to rise – this is not the case for 2025.

“This year, 2025, we’re starting off with kind of a mild landing year, a little bit cooler,” Schmidt said. “So that will be the contrast between 2025 and 2024: we start at a cooler level. So we expect 2025 to be cooler than 2024, but maybe not by much.”

Instead of an El Niño, we’ll start with a La Niña warning, which may lower global temperatures slightly.

Even if 2025 brings a cooler year, the trend is for the earth’s temperature to continue to rise.

Unprecedented wildfires in Los Angeles County are being fueled by unusually dry weather and hurricane-force winds, and experts warn that the problem is not unique to California.

However, it is difficult to know when we will exceed the 1.5 degree limit of the Paris Agreement.

“The general interpretation, including the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, is that pre-industrial means 1850 to 1900, and meeting the target means the average of a 20-year period is above 1.5 degrees,” said Zeke Hausfather , a research scientist at Berkeley Earth.

“The problem with this definition, of course, is that we only really know when we have exceeded the 1.5 degree mark ten years after the 1.5 degree mark has been exceeded, which is not a very useful definition,” he said.

But Hausfather noted that there are climate scientists trying to find a better way to make that determination sooner.

Nevertheless, he said: “We will probably significantly exceed the 1.5 degree mark in the next five to ten years.”

And while it may be tiring to hear that another year is for the record books, no matter where it is, Schmidt said there is a reason for that.

“It’s the same story every year or so because the long-term trends are driven by our fossil fuel emissions and they haven’t stopped,” he said. “Until they stop, we will continue to have the same conversation. And do I sound like a broken record? Yes, I do because we keep breaking records.”

Hausfather is also concerned about the continued rise in temperatures.

“The climate is an angry beast,” he said. “We should stop poking around with sticks.”